Marco Bizzarri

-

Grace Bromley’s paintings explore instability and transformation through a language of ethereal forms and architectural interiors. Built up through countless layers of paint, her compositions dissolve boundaries between body, room, and atmosphere, evoking a world caught between states of matter. Doorways, ever-present and ominous, anchor the work in a quiet, unresolved tension that speaks to domestic space, caretaking, and the inevitability of change.

Grace Bromley (b. 1994, Park Ridge, IL; lives and works in Richmond, VA) holds an MFA from Virginia Commonwealth University and. BFA from The School of The Art Institute of Chicago. Her work has been featured in group exhibitions at Steven Zevitas Gallery, Boston, MA; Jack Hanley Gallery, New York, NY; Mariam Cramer Projects, Amsterdam, NL; LBF Contemporary London, UK; D.D.D.D. Pictures, New York, NY; among others. She will have a forthcoming exhibition with Megan Mulrooney.

Studio Fragments with Marco Bizzarri

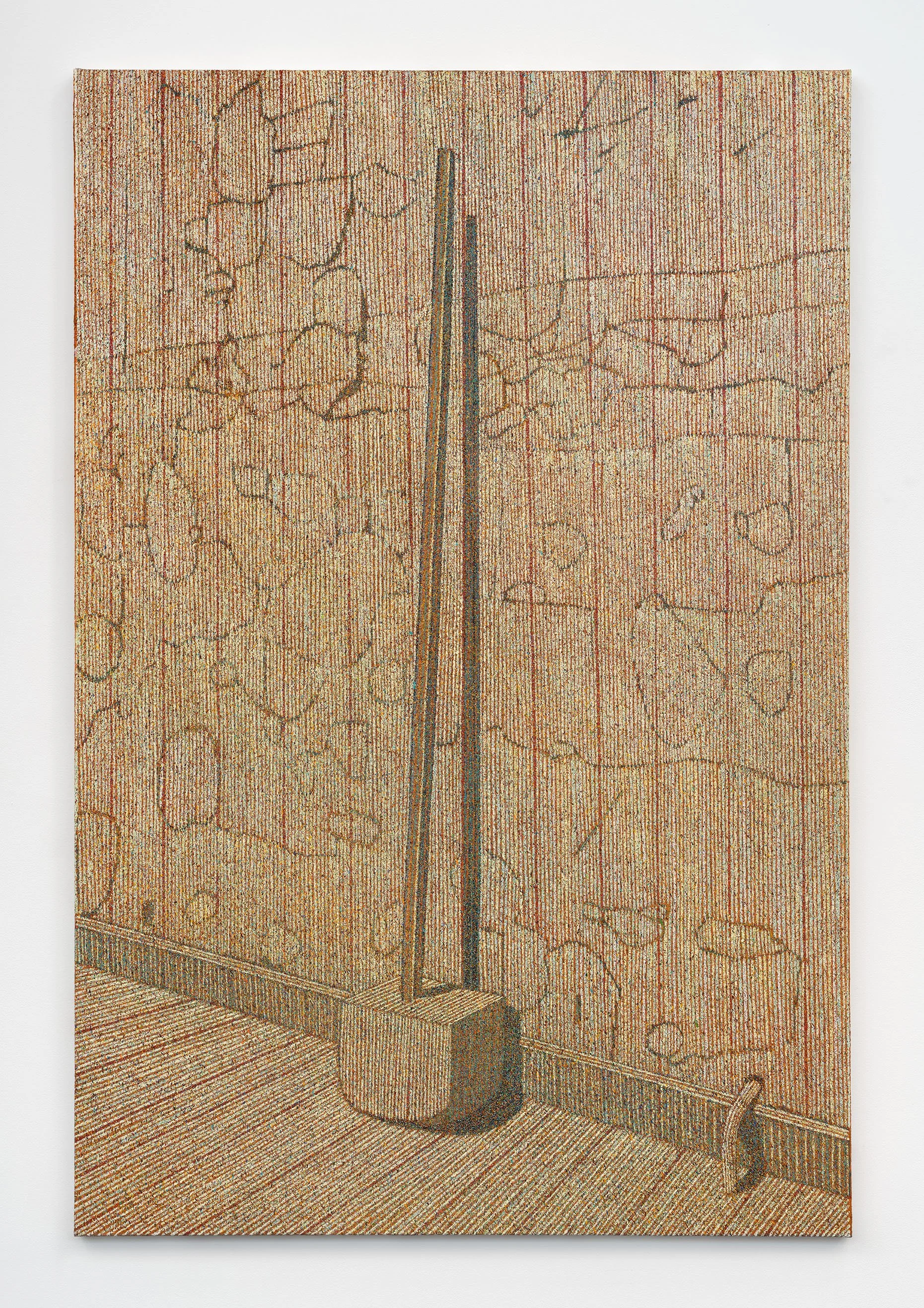

While preparing for his solo exhibition Cielo Abierto, Marco Bizzarri was examining the ways landscape reveals itself when you are fully alone in it: how light behaves in places emptied of human presence, how dust becomes an archive, how ruined architecture opens itself to the sky. Abandoned towns in northern Chile, the vast altiplano, the fields and hills of Sussex, the shifting luminosity inside Gothic cathedrals: these are the environments that shape his imagination. Rather than describing them, his paintings attempt to inhabit their atmospheres, translating their emotional and temporal weight into a sustained visual experience.

What follows are his own writings on the ideas and experiences that underpin this body of work.

I find my inspiration in the landscape of my native Chile. I try to return every year to visit the towns and cities of the north. When I lived in Santiago, I sometimes felt too confined by the city — I would get in a car and escape. Sometimes these escapes were quite impulsive; I wouldn’t tell anyone. Within a few hours, I would find myself in a natural, rural environment, far from people and the city lights. That’s where my work would begin. I always took my camera with me and searched in the architecture of those towns for images that caught my attention — images I wanted to paint, images that posed a challenge to painting, especially in terms of light, shadow, texture, and colour. Lately, I’ve been reading several books. One of them is La luz del sol by Álvaro Galmés Cerezo, in which he explores sunlight as the foundation of our experience of the world. Rather than approaching the topic from a purely theoretical perspective, he moves through the hours of the day in a more experiential way, highlighting how the shifting nuances of light affect both our perception and emotional state. This became especially noticeable to me when I moved to England in 2020. I grew up in a country where sunlight is constant, and I had spent five years working and taking photographs in the driest desert in the world, where clouds are rarely seen.

Our senses and emotions are constantly shaped by the way sunlight interacts with our surroundings — being absorbed, reflected, or refracted within them. This interaction, both on and within objects, in terms of form and colour, plays a crucial role in our emotional, sensory, and perceptual responses, often prompting actions such as pausing and observing.

Perception shifts as sunlight changes. Since it is in constant motion, it causes things to never appear exactly the same — light transforms them. In the book I mentioned earlier, the author introduces the term lumen, not in its technical sense as a unit of luminous flux, but as a more subtle and philosophical way of understanding light — not only as an optical phenomenon, but as a sensitive and revealing presence. This concept has its origins in medieval scholastic thought, where the term lumen creatum — created light — referred to light that is projected into space, making it possible to establish relationships between bodies by defining distance and contour. Within this framework, light ceases to be a mere physical element and becomes a medium through which the invisible is made visible — a substance in itself, perceptible through the liquid or solid particles suspended in the air.

The dry, windy landscapes of the desert, combined with the constant explosions from mining activity, create a dense atmosphere saturated with airborne particles. It is within this environment that light takes on a unique character — filtered and transformed by the floating matter. I began photographing this phenomenon, focusing on the particles themselves, attempting to capture their behaviour, textures, and colours. When analysing the images on my computer, I discovered a surprising combination of intense greens, oranges, blues and magentas coexisting side by side — a palette I later began incorporating into my painting.

In the midst of a personal search around death and loss that I was going through at the time, abandoned spaces began to take on a new meaning. In this context, dust acquired a powerful symbolic value — it became both witness and archive. It holds the memory of what is no longer present — organic matter, bodily remains, fragments of history. Though invisible to the naked eye, those past presences remain suspended, dissolved in the particles stirred by the air and revealed by the light. In this way, dust becomes a carrier of absence — a material form of persistence of that which is no longer visible, something the Chilean desert is uniquely able to preserve due to its extreme aridity. There is something deeply evocative for me in the way light manifests itself through dust. It is an experience many of us remember from childhood — playing in sunbeams that filtered through curtains, revealing, for a few seconds, a universe of floating particles. Over time, this experience tends to fade from our awareness, dimmed by the adult logic that forgets how to look with wonder. But I have returned to that moment again and again — not out of nostalgia, but from a need to recover that genuine sense of wonder through painting.

The customs and traditions of northern Chile are deeply connected to those of Bolivia and Peru, due to shared cultural roots that predate current national borders. Long before the arrival of the Spanish and the later formation of nation-states, northern Chile, the Bolivian altiplano, and southern Peru formed a single cultural region. This is why elements such as music, textiles, architecture, and even the use of colour and light belong to a common symbolic universe that spans the Andes — from southern Peru and Bolivia to northern Chile. From a very young age, I felt deeply drawn to the Andean world. Andean music from Chilean bands was always playing in my home — during my teenage years, and still today in my studio. I especially remember a trip I took with school friends when I was 18, travelling through Peru and Bolivia, always with a camera in hand, documenting everything. It was on that trip that I first discovered aguayos — Peruvian textiles used by women to carry food or children on their backs. I became obsessed with them: their linear patterns and the intensity and symbolism of their colour combinations. I think I bought at least five or six. My friends couldn’t understand why I was so interested in these old, used, stained textiles — or why I was willing to carry so much extra weight in my backpack. Over the years, I continued travelling to northern Chile and Peru, gradually building a small collection of aguayos. Today, when I look at my own work, I realise how my painting has become increasingly linear — almost textile-like in some cases. In a way, I feel that the Andean world and its unique chromatic universe have had a profound influence on my practice. Every now and then, I return to my photographs from trips to the Chilean and Peruvian altiplano. There is always something that catches my eye — something I may not have noticed before — and it sparks new ideas, inspiring me to create new work.

I find a constant source of inspiration in nature. Being outdoors nourishes me deeply — going on long walks and reaching places where there are no people in sight. Ideally, I seek to arrive at some elevated point from which I can take in a wide view of the landscape. In those moments, I become more aware of the light, the surroundings, and the elements. It’s there that my mind becomes clearer. Although it may seem curious, I often compare — and in some way practise — that same experience of deep connection with nature when visiting art exhibitions. That’s why I tend to go to galleries during the week, when there are fewer visitors. The exhibition spaces in London are incredible: the architecture, the lighting, the height, and the enveloping silence all invite contemplation and pause. They remind me of the feeling of entering a Gothic cathedral, where each stained glass window is like a painting hung on the wall, letting light pass through. I live just a block away from a Gothic cathedral — Arundel Cathedral — and whenever I can, I go inside to observe how the light and colours from the stained glass windows are transforming the space. I’m especially interested in how Gothic architecture understood buildings not only as material structures, but as a way of making the intangible visible. Building with stone, yes — but also with light. An aesthetic pursuit, but also a spiritual one. There is something profoundly moving about spaces that contain you — not just physically, but emotionally and spiritually. Spaces that allow you to pause, to breathe differently, to feel held. The cathedral is one of those places for me. Its scale, its silence, and the way light travels through it create a sense of stillness and interiority that I seek both in life and in painting.

There is something of these same sensations when walking through abandoned towns in northern Chile, where light enters in the most unusual ways — the result of collapsed roofs and crumbling walls. I’m drawn to those unexpected and suggestive forms, that random spontaneity of light in all its variations. At the same time, there’s a rush of adrenaline — these places are not without danger. I often find myself captivated by the light, trying to capture the perfect frame with my camera, and in doing so, I can lose awareness of the risks I might be exposing myself to. In a way, there is one artist who reflects these kinds of spaces I encounter while searching for my images: I recently visited The Seven Heavenly Palaces by Anselm Kiefer at the Pirelli Hangar Bicocca. It's a monumental site-specific installation — seven towering concrete structures that evoke both brutalist architecture and ancient temples. They condense a powerful tension between the spiritual and the material, between the eternal and the ruined. Being inside felt like stepping into a space suspended in time. It evokes a deep sense of smallness, of vulnerability — an invitation to slow down, to enter a near-meditative state. I felt as though I could have stayed there for hours, doing nothing. Just looking, thinking, breathing. It’s remarkable how Kiefer manages to evoke, in a fictional space, the same sensations that emerge in real sites of abandonment and destruction. I believe that the same emotional, historical, spiritual, and material weight that we often associate with large-scale spatial or sculptural works is also present in his monumental paintings. Kiefer is, without a doubt, an artist I return to again and again — not because his work offers clear answers, but because it confronts me with essential questions: about time, memory, and matter — the same themes that run through my own practice.

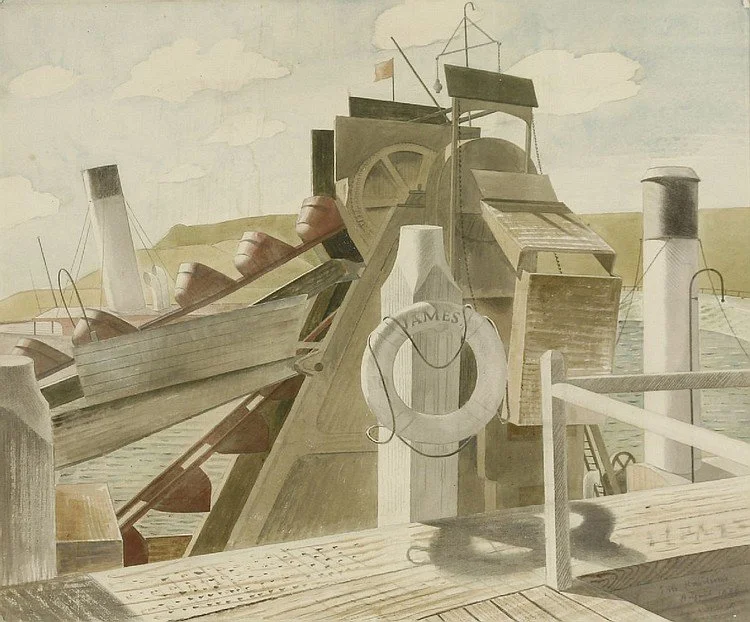

Since I moved to live in Arundel, Sussex, three years ago, there is one artist I simply can’t get out of my head because he seems to be everywhere. Wherever you go — a gallery, a museum, or an antique shop — there’s always a watercolour, painting, print, or postcard of his. That artist is Eric Ravilious, a British painter and illustrator who early in his career devoted himself to portraying the English countryside and everyday life. Later, he was appointed Official War Artist during the Second World War. What fascinates me about his work is how he manages to transform the seemingly simple into something deeply evocative. His paintings are neither heroic nor tragic; they are intimate, contemplative observations, even when set against a wartime backdrop. He approaches both rural landscapes and military environments with the same delicacy, as if both belong to the same quiet world full of hidden meanings. Personally, I am more drawn to his works that contain no human figures. In these, there is a feeling that someone has just left or is about to arrive, as if we are witnessing a moment suspended in time — a “before” or an “after” of something. I feel that this absent presence creates a subtle narrative that makes you feel inside the scene. His watercolours have a unique treatment of light. It seems to envelop the forms in a kind of soft, almost spiritual aura. It’s as if they emanate a white dust, like the dazzling effect on the eye when looking at a white object exposed to sunlight. Ravilious depicted the fields, hills, windmills, and villages of Sussex — places he knew well. As I delved deeper into his work, I found several common threads that have been a great source of inspiration for me. His attention was always on the everyday: empty train stations, solitary lighthouses, sown fields, humble interiors… scenes that he transformed into something worthy of being looked at and remembered.